How To Sprint Faster | A Complete Guide

How To Sprint Faster

How to sprint faster is a topic that's often shrouded in mystery. From gimmicks and click-bait, to downright incorrect information, it can be hard to parse out how exactly one should go about the journey of trying to sprint faster.

Based on my experience as a competitive sprinter and as a track & field coach, as well as research and information from my mentors, this article will detail the things you need to know for you to be able to sprint faster.

Whether you run track, play football, or want to get faster for the sake of it, use this as a resource to help guide you along your journey to sprinting faster.

What This Article Will Cover

- Training To Sprint Faster

- Acceleration

- Speed Training

- Strength & Power Training

- Plyometrics

- General Conditioning

- Frequently Asked Questions About Sprinting Faster

- What are some effective training techniques to improve my sprinting speed?

- How important is technique when it comes to sprinting faster?

- What kind of workouts should I do to increase my speed and power?

- How do I prevent injury while training to sprint faster?

- What are some common mistakes people make when trying to improve their sprinting speed?

- What kind of equipment and gear can help me sprint faster?

- How long will it take to see results when training to sprint faster?

- What kind of mental training and visualization techniques can help me sprint faster?

Training To Sprint Faster

Training to get faster requires that you not only sprint fast, but also build your body up in a well-rounded manner so you can be the best athlete possible. Here we will discuss different forms of training and workouts for sprinters that you can use to sprint faster.

Acceleration Training

Acceleration training is the foundation upon which fast sprinting is built. To reach high speeds, we need to be able to accelerate with a balance of aggression and relaxation, with good technique, and high levels of force production.

Acceleration is typically developed with maximal or near maximal effort sprints in distances ranging from 10 meter to 30 meters. More advanced and experienced athletes may go farther, such as 40 meters, but most sprinters will use shorter distances.

Acceleration sprints can be started from a standing start, a crouched start (such as a 3 point or block start stance), or from a dynamic start. Dynamic starts, such as drop-in accelerations, use less energy, whereas static starts are more specific to the demands of competitive sprinting.

Here are a couple examples of acceleration training workouts that can be used to sprint faster:

- Beginner: 3x10m, 3x20m from a standing start.

- Intermediate: 2x20m from a drop-in start, 2x20m & 2x30m from starting blocks.

- Advanced: 6x40m from starting blocks.

How Should Acceleration Feel?

When we accelerate, we want to focus on being forceful, powerful, and to feel that there is a progression toward a higher stride frequency and a more upright posture & body position over the acceleration distance.

We do not want to pop up on step one, but we also don't want to keep our head down for 100 meters. Emphasize building momentum rather than being as quick as possible or as low as possible. Acceleration sprinting should feel powerful but smooth, aggressive but relaxed.

As far as foot placement is concerned, focus on striking down & back under your chest, not reaching out in front of the body and crashing forward. If you can get your foot to strike under the chest or the hips, accelerating will feel much easier and be faster.

How Often Should You Do Acceleration Training?

Acceleration training should be performed at least once per week as a standalone training session where acceleration is the main focus. You can also add in some acceleration sprints into other sessions, and this can be a good way to ensure you are fully warmed up for performing speed training or speed endurance training.

If you train acceleration on a regular basis, it will help you sprint faster.

Resisted Acceleration Training

You can also incorporate resisted sprint training into your acceleration training, using a sprinting sled, weighted vest for running, or the Exer-Genie. Resisted sprints have been shown in scientific research to help improve acceleration abilities. This can be due to their effects on strength and rate of force development, as well as their impact on skill development.

Resisted sprints can be performed as a standalone session, performed before non-resisted sprints, or as a contrast where you go back and forth between resisted and non-resisted sprints.

To develop early acceleration, such as block clearance and the first few steps, you can use heavier resisted sprints. These may be done with a marching rhythm or as a normal sprint, albeit much slower due to the load.

With these, we want to ensure we are maintaining forward shin angles and working on applying a lot of horizontal force into the track. Heavy sleds should be pulled over short distances, such as 10 to 15 meters.

A heavy sled load could be classified as a load which causes around a 50 percent decrement in velocity, such that the load makes you sprint half as fast as you do without the sled.

To develop mid to late acceleration, lighter loads can be used with longer sprints. Here you will start with aggressive shin angles, but rise gradually over the course of the resisted sprint.

Lighter sled loads should cause a velocity decrement ranging from 10 to 25 percent, with the sled load being appropriate for the distance sprinted. 20 meter resisted sprints may work better with a 20-25% velocity decrement, whereas 30 meter sprints should be done with a 10-15% velocity decrement.

Maximal Velocity Speed Training

While acceleration is what gets you up to speed, the maximal velocity of an athlete is what actually defines how fast an athlete is. As such, you need to perform speed training in order to top speed at which you can sprint.

Speed work early in an athlete’s training year or career will look similar to acceleration sprinting, but be slightly longer. As an athlete progresses, the distance at which they reach maximal velocity will increase, and as such the distance over which we train speed must increase.

It is typically true that faster athletes will reach maximal velocity at a farther distance than slower sprinters, so there should be an organic progression toward longer sprints over time.

Speed is often trained with flying sprints, where an athlete accelerates into a zone where the emphasis is on sprinting in an upright position as fast as they possibly can.

In the first weeks of training where acceleration is trained to 20 meters, speed training may consist of 10 meter flying sprints performed with a 25 meter acceleration zone, making the entire repetition 35 meters in length (25m acceleration + 10m flying sprint zone).

Over time, this will progress to the point where an athlete may be accelerating over 30 to 40 meters, into a maximal velocity flying sprint zone of 30 meters, making the entire sprint 60 to 70 meters in length. This would be a very advanced speed training workout and is a very intense training stimulus.

With speed work, it is important to ensure the following:

- The distance is long enough to allow you to reach maximal velocity.

- The distance is short enough that you do not decelerate significantly by the end of the sprint.

- The amount of work you perform allows for maximal effort on all sprints.

- Once you can no longer run as fast as the previous sprint, you stop the workout or move on to something else such as plyometrics or strength training.

Here are a couple examples of speed training workouts that help athletes sprint faster:

- Beginner: 4 x 10 meter flying sprints with a 20-30 meter acceleration zone.

- Intermediate: 3-4 x 20 meter flying sprints from a 25-30 meter acceleration zone.

- Advanced: 3-5 x 30 meter flying sprints from a 30-40 meter acceleration zone.

To get the most out of your acceleration and speed training, you should progress over time from shorter to longer sprints as your body adapts to training. Earlier in an athletes training career, as well as earlier in their training year, shorter sprints up to 20 meters can be performed. As the athlete improves, they can increase the distance sprinted, as well as the number of sprints performed.

It is suggested that you progress one variable at a time. For example, going from 6x20m to 6x30m would increase the volume of the session by 60 meters. If you increased both the distance and the number of reps, such as going from 6x20m to 10x30m, the increase in training volume would be too drastic. This would increase sprinting volume by 180m, or 150%.

How Should Top Speed Feel?

Sprinting at maximal velocity has a unique feeling that be hard to grasp at times.

Generally speaking, once you have accelerated, your focus should shift toward maintaining an upright posture with a neutral pelvis as you let your legs cycle quickly and you let your feet bounce off of the ground.

When I am sprinting as fast as I can, the main thing I feel is this postural maintenance and the feeling of keeping my feet & ankles stiff so they can bounce off of the ground, applying large forces in short periods of time.

You should not feel yourself pushing backward against the ground. Instead, most of your awareness should be on what is happening on the front side of your body, when the leg is moving downward to attack the ground.

How Often Should Speed Training Be Performed?

Speed training should be trained once per week. Athletes must ensure they are well recovered and have no injuries when they go to perform speed work.

This form of training is very intense and demanding on the body, so your body needs to be ready when you train for maximal velocity. If you abide by these guidelines, speed training will help you sprint faster.

Strength & Power Training To Sprint Faster

To sprint faster, we have to consider the physics involved. The main force we have to overcome in sprinting is gravity, and the strength of gravity is proportional to the mass of an object. As such, the heavier you are, the more force you need to apply to the ground to overcome gravity to sprint fast.

In order to sprint fast, we have to apply large forces to the ground in short amounts of time. While some of this force production can be enhanced by performing sprint training, athletes can also sprint faster by getting stronger, becoming more powerful, and learning to apply force more rapidly.

By incorporating strength training into our training program, we can improve our ability to produce force.

The form of strength training you perform will depend on your age, experience level, and your needs as an athlete.

Beginner athletes need to first learn to move properly using their own body weight or using lighter forms of resistance. Athletes should build competence in various movement abilities, including but not limited to:

- Squatting

- Hinging

- Lunging

- Rotating

- Overhead Pressing & Vertical Pulling

- Horizontal Pressing & Rowing

Strength Training For Beginners

Beginner sprinters can work on these movement patterns first using their own bodyweight in the form of circuit training. Pick 8-12 exercises, perform them for 10-20 seconds each, and then rest for 40 seconds. Once you can perform these exercises in circuits with proper form, with your bodyweight or a medicine ball, you may be able to progress toward loaded variations of these movements.

Strength Training For Intermediate Athletes

Intermediate level athletes who are competent with lighter forms of loading can progress to working these movement patterns with a barbell or dumbbells. For example, a bodyweight or medicine ball squat may progress to a barbell back squat.

A simple guideline athletes can follow with their strength training is the “3 to 5” rule. You pick 3 to 5 exercises, and perform each with 3 to 5 sets of 3 to 5 repetitions per set. As long as the load is challenging, this approach can help you get stronger in a way that is relevant to sprinting.

Stick to larger movements like squats, hex bar deadlifts, step ups, lunges, etc. so that you can activate large amounts of muscle tissue without having to perform 50 different exercises.

Smaller, more regional exercises can also be used to target areas like the hamstrings, hip flexors, calves, and core. I usually program a couple primary exercises as well as a few accessory exercises into my high school athletes’ training programs.

Strength Training For Advanced Athletes

Once an athlete has been training for a long time, more general forms of strength training need to progress toward more specific, more intense forms of loading.

When an athlete makes this progression will vary, but most of the time collegiate or post-collegiate sprinters will need to intensify and specify their strength training to see continued improvement.

Note that if you are still seeing improvement in your sprints with general forms of strength training, you should stick with that until it no longer seems to be working. Regardless, here are some example progressions one might make when shifting to more advanced forms of strength training:

- Range of motion is reduced to emphasize sport specific positions, such as a deep squat progressing into a quarter squat with higher loads.

- Speed of reversal is emphasized, such that you focus on decelerating and accelerating the load as quickly as possible at the bottom of the squat.

- High box step ups at moderate loads progress to low box step ups at high loads.

- Contrasts between heavier exercises and explosive exercises can be used. For example you may pair a heavy quarter squat with a pogo hop, or a deadlift may be paired with a light squat jump. Contrasting exercises can help increase explosive power outputs and rate of force development.

Rate Of Force Development

The further an athlete is in their career, the more their strength training will need to emphasize qualities like rate of force development. This is because, at a certain point, getting stronger over long time durations will not be very relevant to the demands of sprinting.

Earlier on in an athlete’s career, RFD can be trained through sprinting and general forms of strength training. Eventually, though, it must be emphasized more specifically with intense forms of training.

Getting stronger in a lift that takes 500 milliseconds to reach peak velocity may not be very helpful for a sprinter who only has 80 milliseconds to produce force while on the ground in sprinting.

With this in mind, advanced athletes who want to sprint faster should incorporate some lifting in their training which emphasizes rapid muscle contraction and rapid force production.

In my own training, I use progressions to emphasize RFD in different ways. For example:

- Progressing to lower boxes in a step up allow me to reaching shorter times to peak velocity (TPV) and higher levels of RFD.

- Going from a normal quarter squat to a quarter drop squat, where I drop as fast as I can, helps to train eccentric RFD in sprint specific joint positions.

For most athletes, this does not need to be a major focus of their training to get faster. It is in the case of the well-trained sprinter who is no longer seeing progress, that focusing on RFD may be the factor that is needed for them to sprint faster. For beginners, sprinting and basic forms of strength training is all that is needed.

Plyometric Training To Get Faster

Plyometrics are exercises which exhibit rapid eccentric contractions, such as hops, bounds, or drop jumps. If used properly, plyometrics can help athletes become more elastic, bouncy, and help them take their weight room strength and transfer into skills and abilities that allow them to apply force in short periods of time.

For most athletes, plyometric training can be very basic, consisting of low amplitude hopping exercises like pogo hops or line hops. Pogo hops are small hops where the athlete tries to bounce off of the ground as quickly as possible, minimizing any bending in their knees, hips, and ankles upon ground contact.

These can be performed in-place, or moving forward, backward, or sideways. Jumping rope is also a great plyometric exercise that can be implemented early in an athlete’s training career.

Bounding is a more advanced form of plyometric, where athletes move forward over the ground on one leg, alternating between legs, or on both legs. Alternate leg bounds, single leg cycle bounds, or repeated broad jumps are variations of bounding plyometrics.

Athletes should ensure they can manage their posture & ground contacts effectively before they do intense bounding activities. You can start by hopping from foot to foot with a whole-foot contact, only progressing the distance of each hop as your posture & ground contact allows.

Drop jumps and depth jumps are more intense forms of plyometrics that should be reserved for experienced athletes who need a way to intensify their training. Drop jumps are classified as dropping from a height as high as the athlete’s vertical jump, and upon landing they should be instructed to bound or jump off of the ground as fast as they can. Depth jumps are similar, but are performed from heights above their vertical jump.

I generally advise against using depth jumps for most athletes, as the risk of injury is high. Lower drop jumps can give similar benefits, while being less intense. Athletes should ensure that they are very competent at drop jumps before even considering trying depth jumps, and even then they may not be necessary.

General Conditioning For Sprinting Faster

While not a major aspect of training to get faster, some form of low intensity general conditioning can be included in the program. The most common form of general conditioning for sprinting is tempo endurance training.

Tempo in the context of sprinters usually refers to extensive tempo, which is sprints performed at 50-70% speed with short rest periods. This type of training will enhance aerobic fitness, capillary density in muscle, and provide a good stimulus for developing elasticity in the legs.

Example Tempo Workouts:

- 8-12 x 120m at 60% speed

- 10 x 150m at 70% speed

- 6 x 200m at 65% speed

How Often Should Tempo Endurance Be Performed?

These workouts can be performed once or twice per week. The goal is not to become so fatigued that you feel dead afterwards, but rather to simply give the body a way to work on running at lower intensities and to help encourage overall fitness.

Frequently Asked Questions Related To Sprinting Faster

What are some effective training techniques to improve my sprinting speed?

The forms of training discussed earlier in this page are the primary methods of training we use to sprint faster. With that in mind, there are some other things you can do to further spur progress in your sprinting.

One thing you can do is incorporate speed change repetitions into your speed training sessions. If you are performing 30 meter flying sprints with speed changes, you can aim to sprint fast through the first 10 meters of the flying sprint zone, relax for 10 meters, and then finish with another fast 10 meter segment. This can help teach relaxation, as well as give an athlete a feel for the different “gears” they have access to while sprinting.

Another thing you can do to increase the intensity of sprint training is to perform competitive sprints in practice. Running against other athletes helps to increase intensity, add complexity to the sprint, and help to identify errors the athlete may make in high pressure situations. Once an athlete can sprint with good technique while sprinting alone, competitive sprints can be used periodically in practice to further spur development.

How important is technique when it comes to sprinting faster?

Sprinting technique and having proper sprinting mechanics is imperative if you want to sprint faster. Sprinting technique is a big topic, but there are a couple of things you can focus on which will simplify sprinting mechanics and help you improve your technique.

First, ensure that your posture is good. During acceleration, avoid being bent over at the hips such that you can see a straight line from your foot at toe-off up through your hips, spine, and head.

As you rise into upright sprinting, your posture should come to a vertical position, with an upright posture and a neutral pelvic position. Excessive pelvic tilt or an unbalanced spinal posture will make it hard to apply force properly and inhibit your sprinting.

Beyond posture, focus on having active ground contacts rather than passively waiting for the ground. We want to see that the foot attacks the ground in a downward or down & back manner, not letting the foot crash forward into the ground at ground contact.

Novice sprinters tend to smash the ground with their foot moving forward at ground contact, which causes them to overstride, decelerate, and puts them at risk of injury. When sprinting, emphasize a rapid, active downward strike into the ground so that you can apply force well and not disrupt your posture.

By optimizing your posture and ground contact mechanics, you will set yourself up to sprint faster and avoid injury.

What kind of workouts should I do to increase my speed and power?

As discussed, a blend of acceleration training, top speed training, plyometrics training, and strength training will all contribute to you running faster and being a more powerful athlete.

Check out my sprint training programs if you need help putting together workouts to increase speed and power.

How do I prevent injury while training to sprint faster?

Staying healthy and avoiding injury is a major factor in whether or not someone can sprint faster. Sprinting faster requires that you consistently train over long periods of time without interruption. As such, preventing injury needs to be the number one priority in any sprint training program.

The best ways to prevent injury while training to sprint faster are to manage and progress your training appropriately, and to sprint with proper technique.

If you add too much training volume and cannot recover from training, you will put yourself at risk of injury. Sprinting is an intense activity, and you must be fresh with no soreness when you go out to sprint.

Make sure that you do not take yourself to the point of exhaustion in your workouts, that you sequence your training properly to avoid back to back high intensity days, and that you take rest days whenever you feel you cannot put out 95% or better quality on the track.

With technique, avoid overstriding, crashing into the ground, and pushing backward too much when you sprint. If your foot lands out in front of the body, your hamstrings will be put at risk. Similarly, if you push backward for too long, it will lead to overstriding as well as risk injury in your hip flexors.

What are some common mistakes people make when trying to improve their sprinting speed?

There are many mistakes people make when trying to sprint faster, but here are the couple issues I see most often.

First, athletes try too hard to be fast that they end up running tense, with poor timing and no fluidity. To sprint fast, we need to be fluid and relaxed. Learning to put out maximum effort without tensing up is a skill that can only be developed over time. As you go out to sprint, make sure you keep your face, neck, and shoulders relaxed. This will not only help you sprint faster, but also prevent injury.

Second, athletes try to train for sprinting too often. Because sprinting is so intense, we can only sprint fast a few times per week. If you truly want to be faster, then you need to be patient and only load the body with hard sprinting workouts when it is ready and recovered from previous training sessions.

Third, athletes or coaches will do things that they think are speed training which actually have nothing to do with speed. Tap dancing through agility ladders, running 10 x 100m sprints, or doing a bunch of drills are not going to be effective means of improving speed over long periods of time.

Make sure that the demands of your workout are logically derived from the demands of sprinting. If your workouts are not specific to your goals, then it is unlikely for you to see significant progress.

If you are able to sprint with relaxation, perform sprint training a few times per week, and you make sure your workouts are highly relevant to the demands of sprinting fast, then you will have the best chance of sprinting faster.

What kind of equipment and gear can help me sprint faster?

First and foremost, having the right footwear is key if you want to get faster. A good pair of running shoes for sprinting, as well as a pair of sprinting spikes are good to have. Typically you will warm up in running shoes and use spikes for your speed and acceleration workouts. Either can be used for tempo runs, but most prefer to wear running shoes when doing tempo.

For improving acceleration, a sprinting sled, a weighted vest for running, or the Exer-Genie can be useful. These allow you to perform resisted accelerations, drills, bounds, and more. While each of these products vary in their use and form factor, they all can be used for resisted sprinting and other exercises as well.

The tool I use the most in my training is my Freelap Timing System. Whether you pick up a Freelap, something like the Brower Timing System, or you simply use slow motion video to time yourself, having a timing system provides important data that you can use to inform your training program. If you are able to see your times at practice, you can see how many sprints it takes before you become fatigued. Over time, you can see how you are progressing in order to decide how to change your training. Though expensive, timing systems are powerful tools when training to sprint faster.

In the gym, a VBT sensor can be useful for tracking bar velocities, force and power outputs, and rate of force development. Tracking this data can help you decide what loads to use, how much volume to perform, and when to stop the workout. I use a VBT sensor in most of my workouts, and it has helped me select the right exercises, the right loads, and to help manage my volume in the gym.

How long will it take to see results when training to sprint faster?

For qualities like strength and speed, I have found that it usually takes about 6 weeks of consistent training before you will see significant changes in performance. Changes will occur starting on day one, but the most noticeable improvements take some time.

I like to program in 3 week cycles, where the first 2 weeks focus on loading the body, and the third week is a deload with less training sessions and overall less work. If you approach training in this way, it will usually take a couple training cycles before you start feeling much faster.

Because timelines of adaptation vary between individuals and depend on many factors, it is important to stay patient and focus on the long term. If you train consistently, you will be faster 3 months from now. So, focus on the process rather than the outcome, and you will see yourself sprinting faster before you know it.

What kind of mental training and visualization techniques can help me sprint faster?

Visualization for athletes is a crucial but often overlooked tool in the sprint development toolbox. Research has shown that visualization, or mental rehearsal, can help people improve skills and even enhance strength, without physically performing the task practiced.

Since sprinting workloads are limited due to its intensity, athletes can get more training in by performing visualization. When visualizing, make sure that you try to bring as much realistic sensory detail into your visualization, that way it can feel real and be interpreted by your brain as actual physical training.

Over time it will become easier to visualize and execute good sprinting technique in your mind. Doing this daily can give you extra opportunities to enhance your confidence, technique, and will help you sprint faster.

References

- Behm, D. G., Young, J. D., Whitten, J. H. D., Reid, J. C., Quigley, P. J., Low, J., Li, Y., Lima, C. D., Hodgson, D. D., Chaouachi, A., Prieske, O., & Granacher, U. (2017). Effectiveness of Traditional Strength vs. Power Training on Muscle Strength, Power and Speed with Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in physiology, 8, 423. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00423

- Bolger, R., Lyons, M., Harrison, A. J., & Kenny, I. C. (2015). Sprinting performance and resistance-based training interventions: a systematic review. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 29(4), 1146–1156. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000720

- Liao, K. F., Wang, X. X., Han, M. Y., Li, L. L., Nassis, G. P., & Li, Y. M. (2021). Effects of velocity based training vs. traditional 1RM percentage-based training on improving strength, jump, linear sprint and change of direction speed performance: A Systematic review with meta-analysis. PloS one, 16(11), e0259790. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259790

- Guizelini, P. C., de Aguiar, R. A., Denadai, B. S., Caputo, F., & Greco, C. C. (2018). Effect of resistance training on muscle strength and rate of force development in healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Experimental gerontology, 102, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.11.020

About The Author

My name is Cody Bidlow. I have been sprinting and coaching in Track & Field for the majority of my life. One of my life purposes is to share what I have learned, so that other people can benefit.

If you enjoy content like this, consider visiting my YouTube channel, Instagram account. If you need help with your sprinting, check out my training programs, online training group, or my coaching consultation services.

Online Training Group

Get workouts sent to your phone to help you get stronger, sprint faster, and jump explosively.

Sprint Training Articles

View all-

Training For Speed - Methods, Progressions & Ti...

Speed training is fundamentally the primary way to train in order to sprint faster. Social media influencers and coaches throw the term speed training around loosely, when in reality it...

Training For Speed - Methods, Progressions & Ti...

Speed training is fundamentally the primary way to train in order to sprint faster. Social media influencers and coaches throw the term speed training around loosely, when in reality it...

-

How Should Sprinters Train In Their Off Season?

After a long season of training and competition, many sprinters find themselves wondering what they should do once the season has come to a close. Some continue to train hard,...

How Should Sprinters Train In Their Off Season?

After a long season of training and competition, many sprinters find themselves wondering what they should do once the season has come to a close. Some continue to train hard,...

-

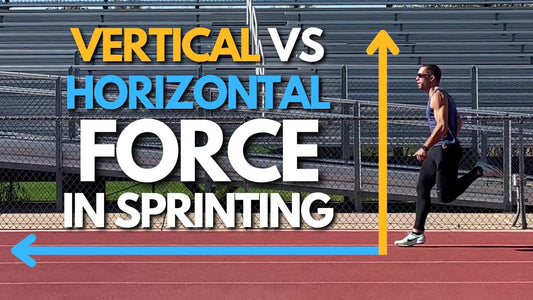

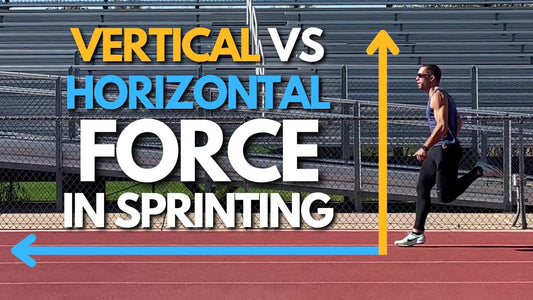

Force Production In Sprinting | Is Vertical Or ...

In discussions surrounding sprint performance, coaches and researchers have debated whether vertical force or horizontal force is more important for running fast. While many will pick a side and claim...

Force Production In Sprinting | Is Vertical Or ...

In discussions surrounding sprint performance, coaches and researchers have debated whether vertical force or horizontal force is more important for running fast. While many will pick a side and claim...

Sprint Training Programs

-

100 Meter Dash Training Program Off-Season & Pre-Season Bundle

Regular price $47.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$99.00 USDSale price $47.00 USDSale -

400m Dash Off-Season & Pre-Season Training Program Bundle

Regular price $47.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$95.97 USDSale price $47.00 USDSale -

200m Dash Off-Season & Pre-Season Training Program Bundle

Regular price $47.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$95.97 USDSale price $47.00 USDSale -

Indoor Off Season Bundle - 60 Meter & 200 Meter Dash GPP Training Programs

Regular price $62.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$78.00 USDSale price $62.00 USDSale